Will KPMG seize their second chance with Canadian private debt investors?

The audit firm faces a tough decision

“Auditors are supposed to know the business they are auditing, including the general economic, business, and fundraising environment. But they should look at that info and management’s pronouncements with professional skepticism.” — Francine Mckenna (@retheauditors)

As you can see from my writing, I have been a strong critic of private debt funds sold in Canada to retail investors. I believe that Bridging Finance is not a lone bad apple in the industry but one of many that have abused investors’ trust and asset class characteristics. By using aggressive accounting practices, Bridging and many other private debt managers have disguised the reality of their loan portfolios.

Bridging Finance’s receivership reports confirm that the asset value of their funds was significantly overstated by more than 50%. And Ninepoint Partners, the leading promoters of private debt funds for retail investors in Canada, has decided to cancel redemptions in some of their private debt funds. Both incidents highlight the risks in these types of investments. Both events put KPMG under the microscope as the auditor for these funds.

Private loans are illiquid and are considered level 3 securities under accounting principles. According to Investopedia, level 3 assets are the “hardest to value” by combining “complex market prices, mathematical models, and subjective assumptions.” In other words, you will need to trust those who appraise them. This aspect of the asset class is what creates problems for investors. As stated by author Dan Davies in his book, Lying for Money, “where there’s trust, there’s the opportunity for fraud.”

Bridging Finance’s investors used the financial statements, audited by KPMG, to value their holdings. KPMG was supposed to be an outside check on Bridging management. But in reality, KPMG relied on the valuation methodologies used by Bridging management — which also determined Bridging’s compensation. So, in the end, it was a chain of trust extending from Bridging investors back to Bridging management. Might this lead to KPMG being overly deferential to Bridging Finance’s management?

Just 30 days before a Court placed Bridging’s funds into receivership, amidst several fraud allegations, KPMG issued a clean opinion on the Bridging Income Fund financial statements. The opinion said Bridging’s financial statements “present fairly, in all material respects, the financial position of the Fund as at December 31, 2020.” Today, the same balance sheet is facing a loss in value of up to 67%.

In his book, Davies explains, “[fraudsters] play on weakness in the system of check and balances, the audit processes that are meant to supplement an overall environment of trust.” Short-seller Jim Chanos says, “almost every fraud has been audited by a major accounting firm.” All this means that securities fraudsters know how to exploit the role and weakness of an auditor.

As investors, we expect auditors to act as a safeguard against fraud. However, Kris Bennatti, a former auditor, data scientist, and now founder of Bedrock AI – a firm that uses machine learning to support corporate accountability through information transparency – disagrees. She says, “audit firms don’t actually think it’s their job to find fraud.” One of the reasons for this belief is “that even a well designed audit will have to rely on management’s representations at one point or another”

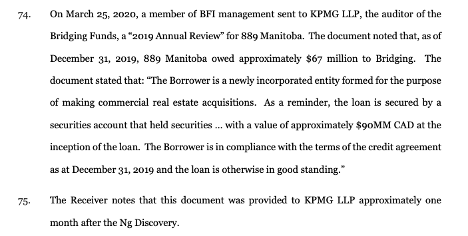

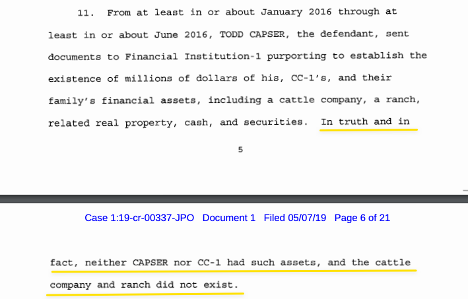

Bridging’s receiver report provided some glimpses of the auditing process between KPMG and private debt funds. The receiver detailed how Bridging’s management made representations to KPMG. Specifically, in relation to $67 million in loans advanced to 10034889 Manitoba Ltd (889 Manitoba), a corporation owned by Gary Ng. On February 26, 2020, Bridging management discovered that the collateral backing that credit didn’t exist. Bridging’s receiver says:

Extract from the Tenth Report of Bridging’s Receiver

Those audited financial statements were issued without a qualified opinion. To be fair, KPMG had no way of knowing at the time that Gary Ng had already fooled several asset managers in North America. Nevertheless, this shows how KPMG relied on a document provided by the fund manager to test the quality of the loan. According to the fund’s OM, the same fund manager was responsible for the loan valuations. Bridging’s management knew they were misrepresenting the facts but probably figured that a document was enough to cover their mistakes and keep charging millions of dollars in fees.

The receiver also described how Bridging management believed that a public association with Gary Ng “would be detrimental to the future success of Bridging.” The Sharpes knew that the public would wake up and see that their claim of not realizing a loss was a lie. A claim that is impossible to live up to when dealing with investments as high-risk as private loans with double-digit interest rates. Worryingly for investors, David Sharpe is not the only private debt manager claiming to have an immaculate, loss-free record.

There is little doubt that Bridging Finance preyed on KPMG’s weakness and lack of professional skepticism to hide their losses for so long. The audited financial statements didn’t represent the economic reality of the funds. Seven months after signing the last one, KPMG withdrew their opinion from Bridging’s financial statements.

Even when Bridging’s underlying proposition sounded too good to be true, KPMG didn’t apply their independent judgment to overcome the natural tendency of over-relying on the client’s representations. They took Bridging’s representations at face value. By just performing a Google search on the top borrowers’ names, KPMG would have realized the financial reality of those counterparties.

Recently, PwC, as receiver for Bridging, published their comprehensive findings of the pervasive deficiencies across Bridging’s loan portfolio. The PwC report classified the deficiencies into five key categories: (a) payments-in-kind; (b) extension of more credit when the borrower was struggling; (c) credit bids related to insolvent borrowers; (d) concentration of risk to economic groups under different loans; and (e) failure to disclose conflicts of interests.

Here is where an uncomfortable situation arises for KPMG. Many of the same deficiencies described by PwC can be observed and independently verified in several other private debt funds in Canada. Many of those funds are audited by KPMG, including the ones marketed by Ninepoint Partners from investment managers like Third Eye Capital (currently gated) and AIP Asset Management. These managers use aggressive accounting and valuation practices on their assets. You don’t have to take my word for it; they are just a Google search away. OPM Wire private debt coverage is a good place to start.

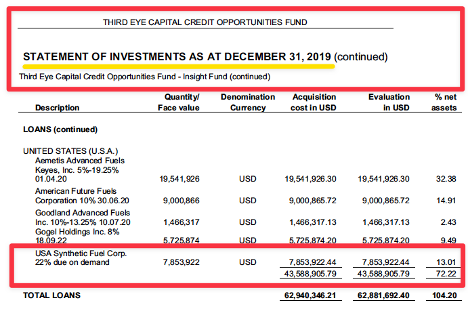

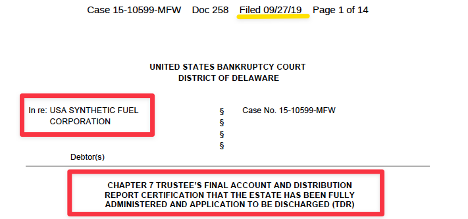

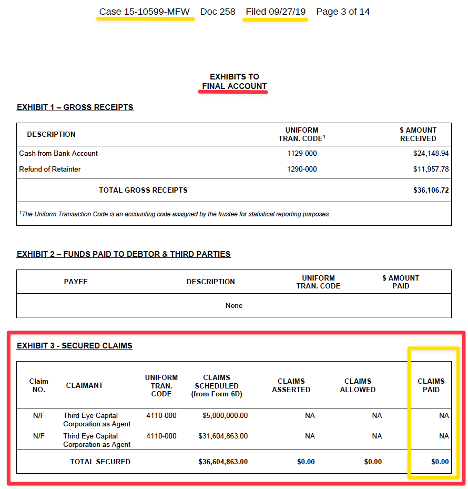

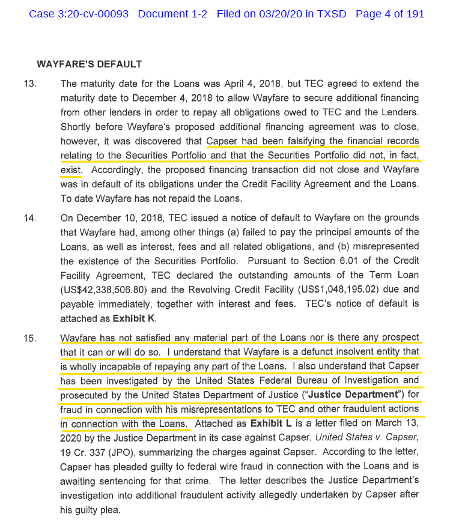

As an example of these aggressive practices, Third Eye Capital Credit Opportunities Fund’s accounts, audited by KPMG for the period ended on December 31, 2019, show a loan at face value to USA Synthetic Fuels Corp. USA Synthetic Fuels Corp was a corporation financed by Third Eye Capital in 2012. The company went into Chapter 7, and the Bankruptcy Trustee filed their final account (i.e. the corporation ceased to exist) on September 27, 2019. That means that the entity was defunct, when the loan appeared on the fund’s balance sheet, at face value. The final reports show no payments to Secured Creditors (i.e. Third Eye Capital) during the liquidation.

Extract from Third Eye Capital Credit Opportunities Fund audited accounts as Dec 31, 2019

Extracts from USA Synthetic Fuels Corp Trustee’s Final Account and Distribution Report.

Extract from Capser’s indictment from May 2019.

Extracts of an Affidavit sworn by Mark Horrox on March 16, 2020.

Reported sales of tankers by Compass Maritime for the week of November 4th, 2021

IOTA’s market cap has cratered from over $90 million twelve months ago to over $3 million today. The CFO resigned last January, and the auditor recently withdrew their opinions for fiscal years 2018 and 2019. All of this while the company faces an action from the SEC for their delinquent periodic filings.

While all this happened, AIP has not created any provisions for the IOTA investment or even for their entire portfolio of deficient borrowers (e.g. Elixxer, ZoomAway, Relevium Technologies and a subsidiary of Tetra Bio Pharma). Even if they claim to have senior security over IOTA, that doesn’t guarantee the collection of their investment, as previously explained in The Myth of Senior Security.

AIP Convertible Private Debt Fund Q4 2021 Commentary. Source: AIP

***

It is a matter of time before we see Bridging’s receiver suing KPMG for dropping the ball and missing so many red flags. In the last six months, investors from The Abraaj Group and Carillion, have filed court actions seeking almost C$3 billion in damages from KPMG. These investors alleged that the audited financial statements were “seriously misleading.”

Could KPMG argue it was a victim of David and Natasha Sharpe? Maybe. But what if another Canadian private debt fund audited by KPMG ends up in a receivership resulting in material losses for investors because of their aggressive accounting policies and underwriting deficiencies? “Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me.”

So, in my view, in the coming days, KPMG will be facing a tough decision. Will they take the risk of issuing more clean opinions when the market is running away from some of the private debt funds they audit? Will they scrutinize the aggressive management representations? They are walking a tightrope. Issuing a clean opinion to these struggling funds might make them accomplices of the eventual losses that could arise if these funds end up in receiverships.

My initial reaction was that KPMG would raise their level of professional skepticism and think twice before issuing their opinion. But a renowned securities fraud investigator recently told me that auditing is a business like any other; auditors have to meet short-term revenue targets. On the other hand, if monetary sanctions come, they will arrive years later when it is likely that the partners responsible have left the firm. So, most of the time, auditors don’t have the incentives to walk away from uncomfortable positions. The conversation was eye-opening and depressing.

Will KPMG side with investors who trust them, or will they side with those who pay them? We will have to wait a few weeks to see what happens.

Once KPMG issues their opinion on the financial statements of Canadian private debt funds, I will be happy to provide to any investor my view of the accuracy of those statements, free of charge. You know where to find me.